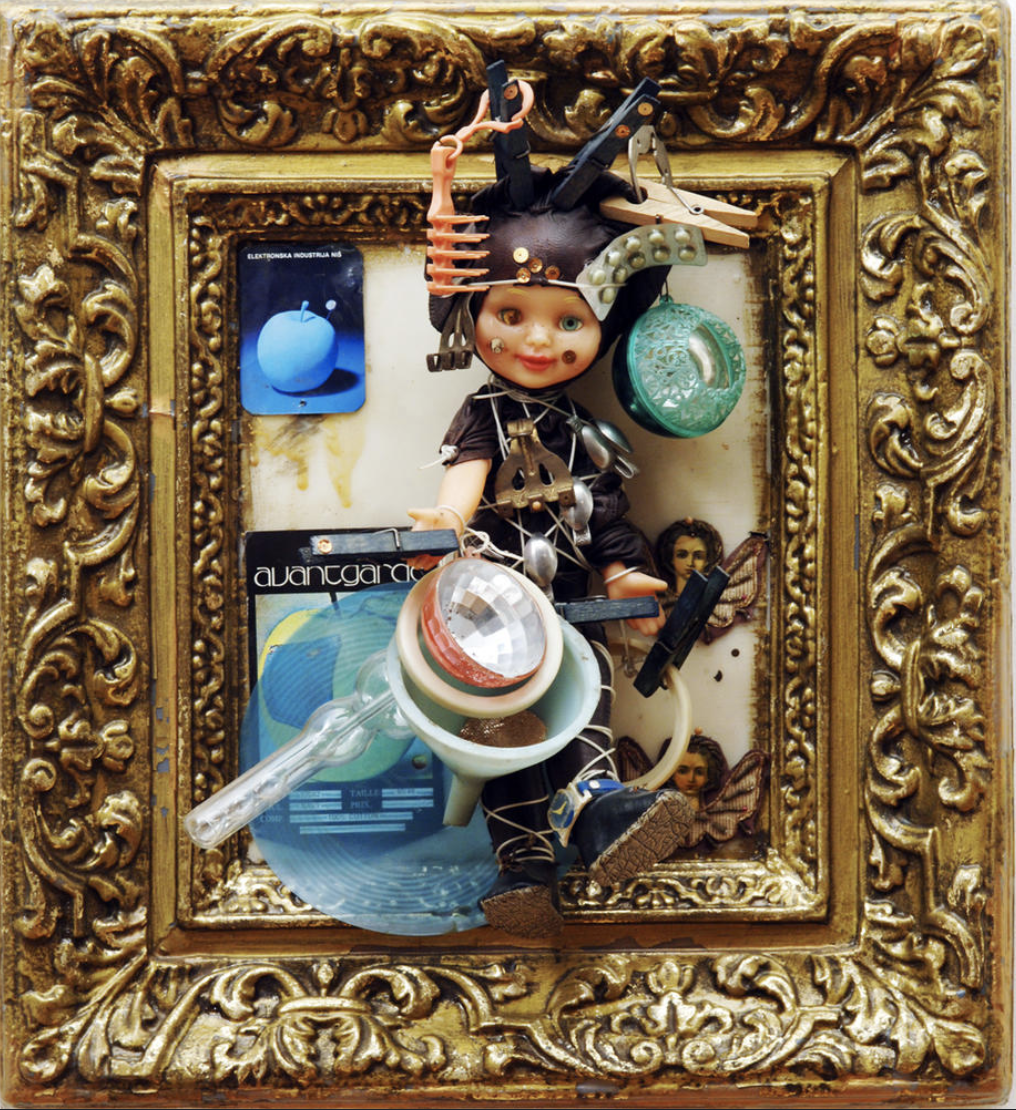

Sergei Parajanov House-Museum

November 26, 2019

Our Favorite Ways to Relax

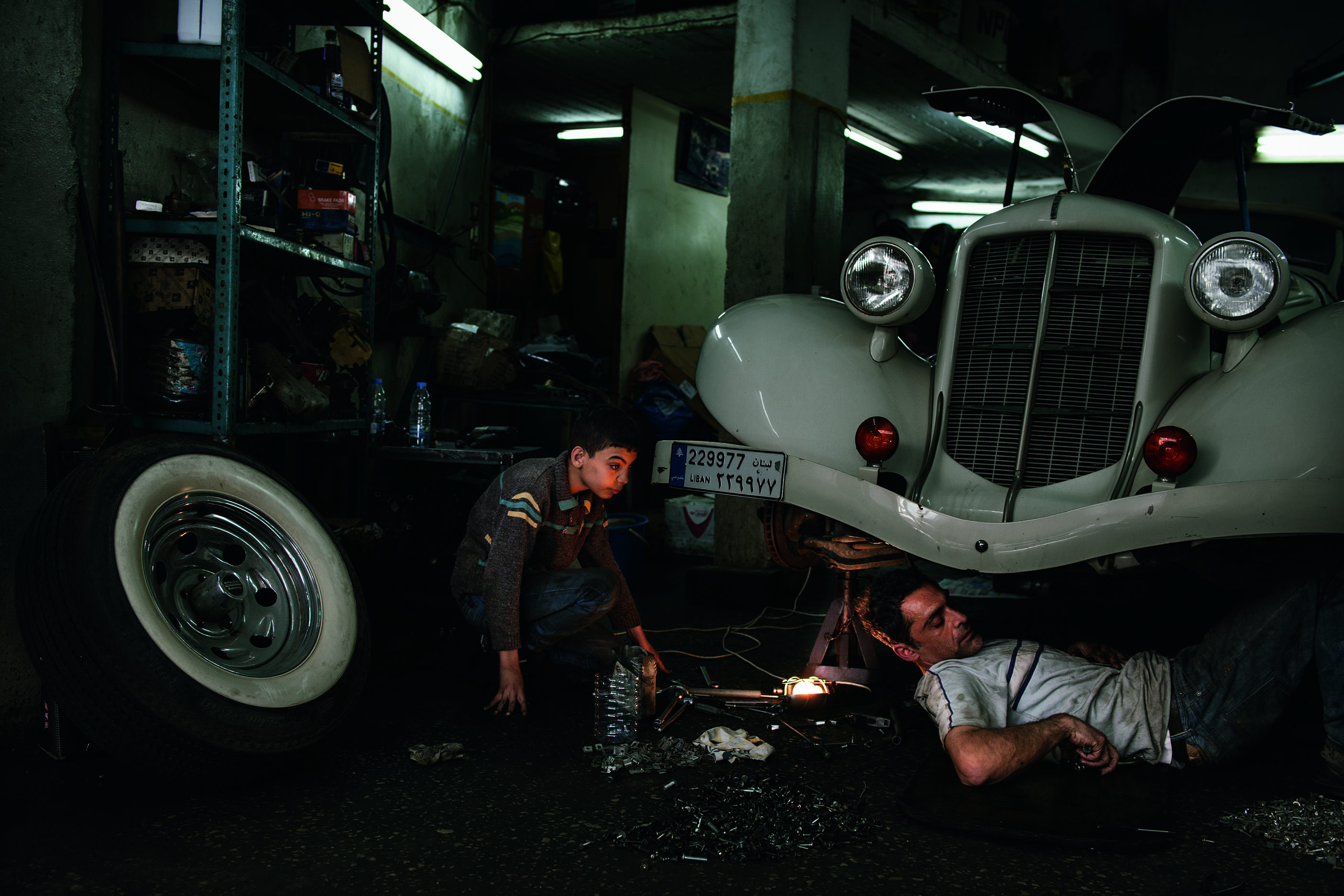

December 2, 2019I had the exceptional opportunity to have a conversation with Erhan Arik, a social documentary photographer who dedicated many years of his professional life to silently capturing the history of Armenian Diaspora living near the borders and in the Middle East. His projects Horovel and Gayan were exhibited in different countries including Turkey and Armenia.

I would like to hear about your journey and about the moment you knew you wanted to be a photographer?

Erhan Arik: It is a funny story. I wanted to be a painter and study at an art school. When I was taking my entrance exam, I looked at the person next to me. He was so engaged in the process of painting as if he were flying and his movements made me realize that I was not talented enough. Therefore, I did not succeed in painting and started looking for a form of art that would interest me. That’s when I found photography. To become one, I had to take an exam, but the examination process had turned into trauma for me. Instead, I decided to study Journalism at Anadolu University in Eskişehir and that way also to take photography classes. After a year, all my courses were about photography: documentary photography, photojournalism, etc. I was very lucky because my teacher of social documentary photography was Merter Oral, an important figure in this field in Turkey. That’s how I started to focus on social documentary photography. Today, I am very happy that I am a photographer, but I still paint sometimes. Painting helped a lot in my journey as a photographer.

Avrizurk Armenian village, North Iraq

How was the idea of Gayan born? How did a single dream turn into this long project?

Erhan Arik: You may say that this journey started from just a dream, but it was not just a dream for me: it also combined history, culture, my family, myself.

My family is from Akhaltsikhe, South Georgia and they moved to a village in Ardahan, Turkey around 1930. As we know, the village was Greek-Armenian, and most probably Armenians moved from there during the 1915s and Greeks moved away later. I knew from my grandfather and father that our house used to be an Armenian house, just like the other houses in the neighborhood. It was in 2009 when I had a dream about it. In the oldest room of the house, there was an oven (օջախ) where we used to keep our animals. The man in my dream told me that it was his house, and they used to cook and play in that same room which we were using as a barn. In our culture, the oven symbolizes a lot of things: family, past, future: it is very important. But my family did not take that into account.

Afterwards, I started to criticize everything, especially myself. I was very engaged in social issues in Turkey and I was working for Hrant Dink but by that time he was already killed. In my daily life, I was someone who was interested in all these social issues, but in my private life I couldn’t find myself and I had all these thoughts regarding the barn. Back then I knew only one Armenian journalist Pakrat Estukyan, who was working for Agos newspaper. I met him, told him about my dream and that I wanted to go to the Armenian villages near the border. He told me to also visit the border villages from Turkey’s side and to record horovels. I did not know what horovel was, so he suggested that I visit my father before my journey, tell my family about my dream and asked my father what horovel was.

After I talked to my family, they were silent. My father suggested cleaning the barn, but for me, it was not just about the barn. I asked him what horovel was and he explained that it was a Turkish song that was sung while working in the farm with animals. It was quite complicated because he knew what horovel was but he did not know it was Armenian or maybe others didn’t want us to know that it was Armenian. That’s when I understood that the main issue was that people didn't know those stories or didn’t want to remember those stories connected to Armenia.

So, my journey of Horovel started. During this first phase, I visited 10 villages from the Turkish side and 13 villages from across the Armenian border. In Armenia, I started listening to people, listening to their stories of Genocide time, stories of second and third generations. I met a woman, Tigranuhi Asatryan, a Genocide survivor, whose stories affected me very much. Although I never intended to embark on a long journey, I decided to continue exploring outside of border villages.

Bourj Hammoud, Beirut

What role did your nationality play during this project? What were the feelings of those you photographed?

Erhan Arik: Before even starting this project, culture was very important to me. I didn’t care if I was Meskhetian, Caucasian, Georgian, Armenian. I told my friends that I was lucky to be from the Caucasus, as there is no clear identity here. But when I started the journey, the first question was: are you Armenian or Turkish. I am a social documentary photographer, so when I meet people I have to explain everything to them. Even if they don’t let me take their photo and write their stories, it doesn't matter. For me, the end result is not what is important, the process and people’s stories are more important. After their questions about my identity, I started to question who I am. I started to explore my roots. We have that issue of identity in Turkey, as not all are Turks, there are many nationalities behind that. In this journey, being a non-Armenian was key to talking to people. They shared their anger and genocide stories. After my first trip to Armenian border villages, I decided to revisit again. Surprisingly, this time they started asking me more personal questions, about my family and my daily life, which meant a lot to me.

Wedding in Istanbul

How did people react to both your projects Horovel and Gayan (Kayan)? How did it resonate with people?

Erhan Arik: I opened the exhibition of Horovel about the border villages in 2011 and Gayan focused on Middle Eastern diaspora and it will continue in Europe and the US. Back in 2011, this was a very sensitive issue, thus reactions were different. The most common response was silence, people were just listening. Some people found it propagandistic, thought I documented the stories from only the Armenian perspective and showcased it very directly and straight. Others understood that there was a problem, but did not want to discuss it in detail. But Gayan was perceived differently. People liked how I silently captured the stories and memories. Others wanted to see more of myself and my feelings in the photos and did not find it very artistic. Yet, only a small percentage wanted to talk about the Genocide.

Armenian Band

In Nor Jugha

Do you think people you’ve met are still in “Gayan” (Kayan)?

Erhan Arik: I think diaspora Armenians have different character traits in different regions. Even in the Middle Eastern countries, it can be different. But the common thread, I have noticed, is that they don’t want to move away from where they are. They don’t want to have to leave again. But at the same time, they don’t feel like that's their home. It is a contradicting feeling.

After all these years, what did this journey and this project give to you?

Erhan Arik: I have come to understand what we lost regarding cultures, society, living together and facing our history and our issues. The Armenian Genocide is the most symbolic issue of Turkey. After the Genocide, they started to create this fake culture full of many social issues and I think that if we face what happened in 1915, it will change a lot. My journey is still going on and it brings many complicated situations. When you focus on your memories, there are so many: memories that you have, memories that society teaches you and collective memories of your family. Sometimes they are confronting. Yes, today I am fine because I am not accepting everything that the society teaches me and I am going to fight for these issues. Still, there is a lot of angriness inside of me. Before that dream, I knew that it was my village, I liked it and it was very important to me, but after that dream, that house is not the same for me. There are so many things that are not easy to explain. For me personally, I have realized what we lost.

So, what is next? How will Gayan continue?

Erhan Arik: I am really focused on completing this journey. Sometimes I think maybe I need to take a break and concentrate on other issues, but till now I am only able to concentrate on this. At the end of this year, I will travel to Marseille, France and will continue exploring Europe and the US for the next three or four years.

Birds Nest Orphanege

Bella is an economist passionate about Asian and developing economies. Apart from academics, she is interested in human rights and education. Bella is fascinated by abstract expressionism, modern art and enjoys quality music.