Where to find the best Zhingyalov Hats

November 3, 2019

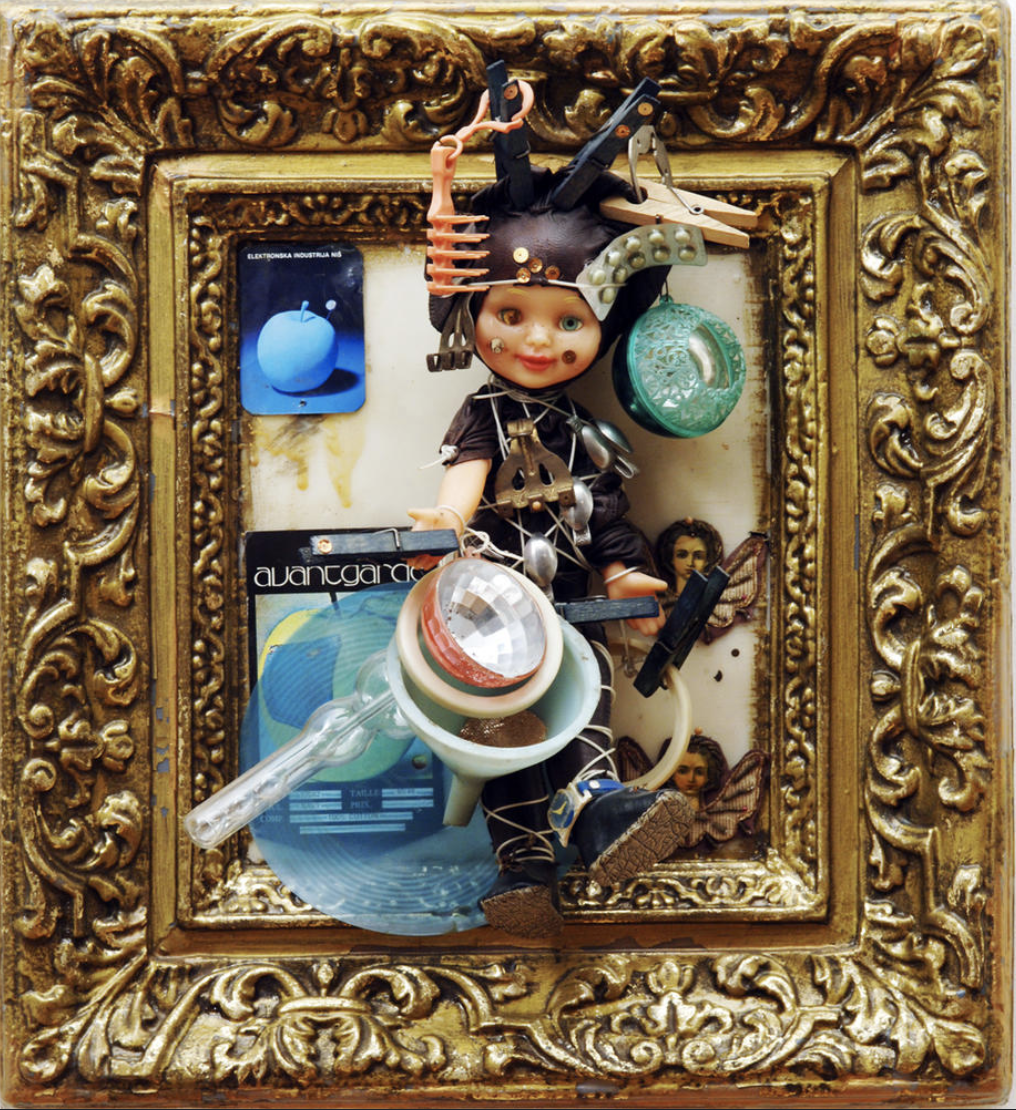

Sergei Parajanov House-Museum

November 26, 2019Araks Sahakyan has an interesting presence. The more you spend time talking with her, the further she seems to move away from you. As if she's there, sitting in front of you but it's so obvious that her depth is more than you can grasp in one sitting.

"Salomé", video, 25', from the series "Mythologie Vivante - Mythologie Feminine". Co-directed with Ramón R. Carpena.

How was the transition from a translator to an artist?

Araks: I would say it was quite natural. I studied the art of translation for five years and upon my graduation from university, I got a chance to do an internship at a publishing house in the South of France. My job was translating articles about theatre and performers. It is believed that translation is the best form of reading. The life and work of the artists I was translating about affected me greatly and I decided to do some video experiments. I got carried away to the extent that I decided to study fine arts.

A few years ago I came across a quote by translator Janine Altounian. It said: “All children of survival are condemned to translate”. It must have resonated with me as I went into studying translation when I was 18. And translation in its turn, eventually, brought me to fine arts.

You have a video about the Armenian Genocide in a language that you invented. Can you tell us about it?

Aaks: I moved to Spain when I was 13 and only returned to Armenia when I was 23. Growing up I've always had identity problems. But it became more evident as I returned to Armenia. People remembered me as I left the country as a teenager and expected to see the same girl.

While in Armenia, something prompted me to take a solo trip to Turkey, as I felt my identity crisis might somehow unfold during the trip. I filmed everything I saw: the old Armenian cities and settlements, nature, etc. There was a lot of random stuff as well. Once back at home, as I edited and watched the video montage, I realized I’d been talking out loud about my feelings.

The video was not about the Armenian Genocide. I didn’t want to know why it happened. All I wanted to understand was how did people continue living on that land after the events. In order to understand your own identity you have to explore “the other”, in this case - the Turks. However, there was no suitable language to communicate my emotions and feelings. I wanted to speak in Armenian and that made me feel a 13 year old again. Spanish wasn’t working either as my childhood wasn’t spent there. I knew a lot of languages but there was no language for me. So I started to tell a story in an invented language. I tried to speak in that language later but it was not possible.

Do you remember your first drawing as a kid? Do you think that your parents’ reaction to your drawings as a kid was a motivation to never stop drawing?

Araks: I don’t remember my drawings but I remember my felt pens. I used to draw with felt pens and I liked that a lot. When I was a child I didn’t really expect to become an artist. As for my parents, they never gave full attention to my drawings.

PHOTO from BIC prize: © Lucie Taccard

PHOTO from exhibition "Out of the shadows": © Xavi Civera

What or who was your biggest inspiration during the first years of your work?

Araks:I don’t have any big inspirations because I get all my inspiration from my personal daily life and also the daily lives of collective people. So what I see when I go outside, my memories of Spain or Armenia are inspiring me and now that I’m in Paris what I see inspires me.

But I can give some diverse references. I liked some of Anna Akhmatova’s poems, I love the poetry of Garcia Lorca, I like Julio Medem’s films, they were really important in my adolescent life. And also Pedro Almodóvar’s films full of imagination and aesthetics. There’s an Italian theater director Pippo Delbono, it was a really big encounter with his work when I saw his theater performance videos in Paris in an exhibition at a museum for art brut / outsider art La Maison Rouge. His work was really inspirational. And of course in music, my inspiration was always Komitas. For me, the music of Komitas is nothing about religion but about the spirituality and soul. I sing in a choir in Paris so his music is really important for me.

Do you think that the French environment helped you start creating or vice versa caused many obstacles in your way?

Araks: It is difficult to integrate into Paris because it’s a wild wild wild city. I've been living here for already 5 years but it’s only now that I feel integrated. Of course, it’s inspiring but sometimes it can also be an obstacle because you get lots of problems that you need to find a solution to very fast, otherwise, you’ll be lost. But still, I like the environment of Paris for my creative process.

Have you ever worried about whether or not people will understand and accept your creations?

Araks: It’s like one of the most important questions in creation. Because even though we say that I’m the artist and I arrived in the art for a reason, when we create something and show it we want to get feedback. So opinions are pretty important and sometimes I even think I pay too much attention to them but in the end, I always do what I wanted to. Even if it hurts some opinions I do “eshi pes” whatever I planned. I guess all artists should have a stubborn donkey in their minds.

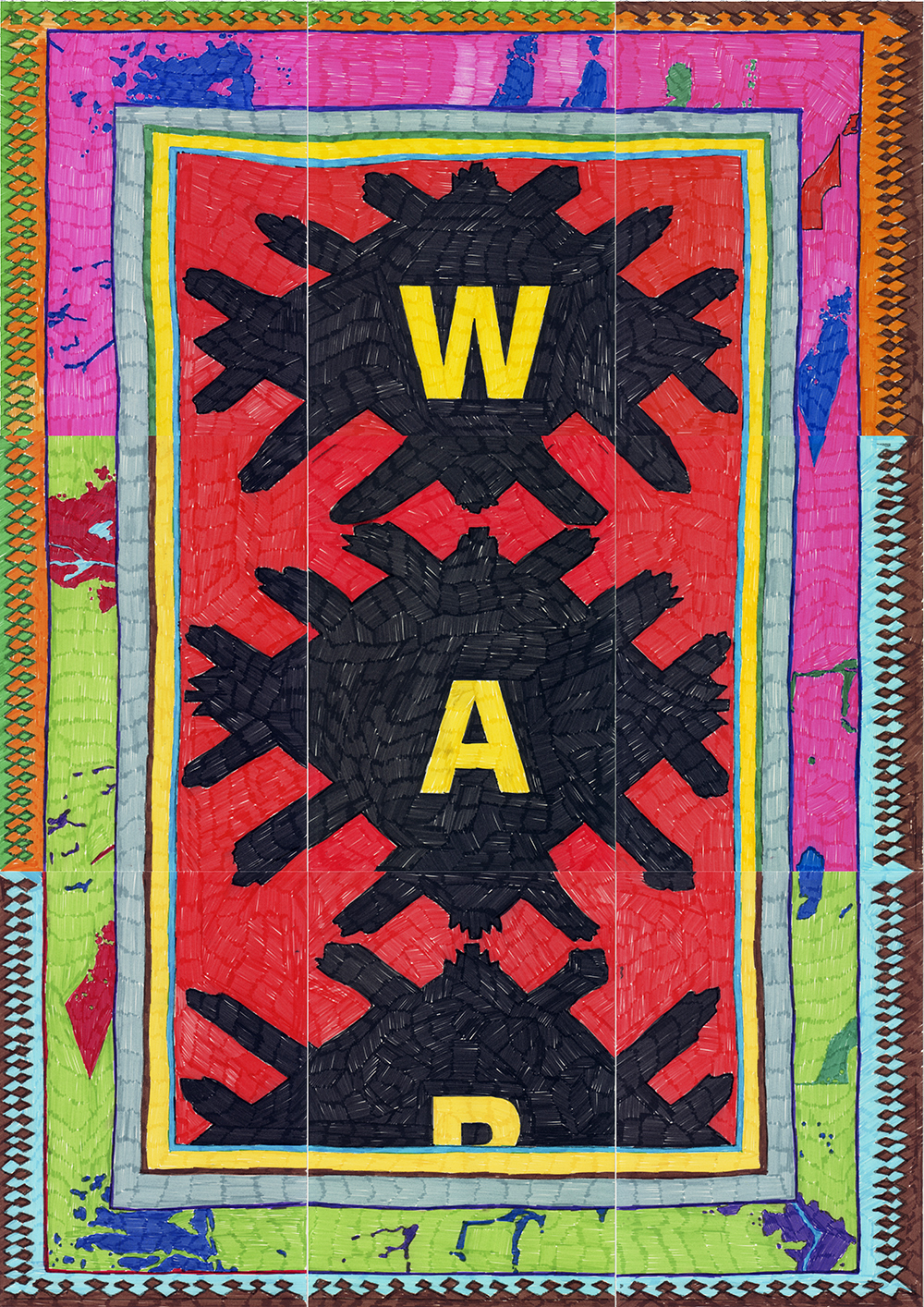

War 9 sheets. Dimension of paper carpet: 63x89.1 cm

121 sheets. Dimension of the box: 23x33x5cm. Dimension of paper carpet: 213x301cm

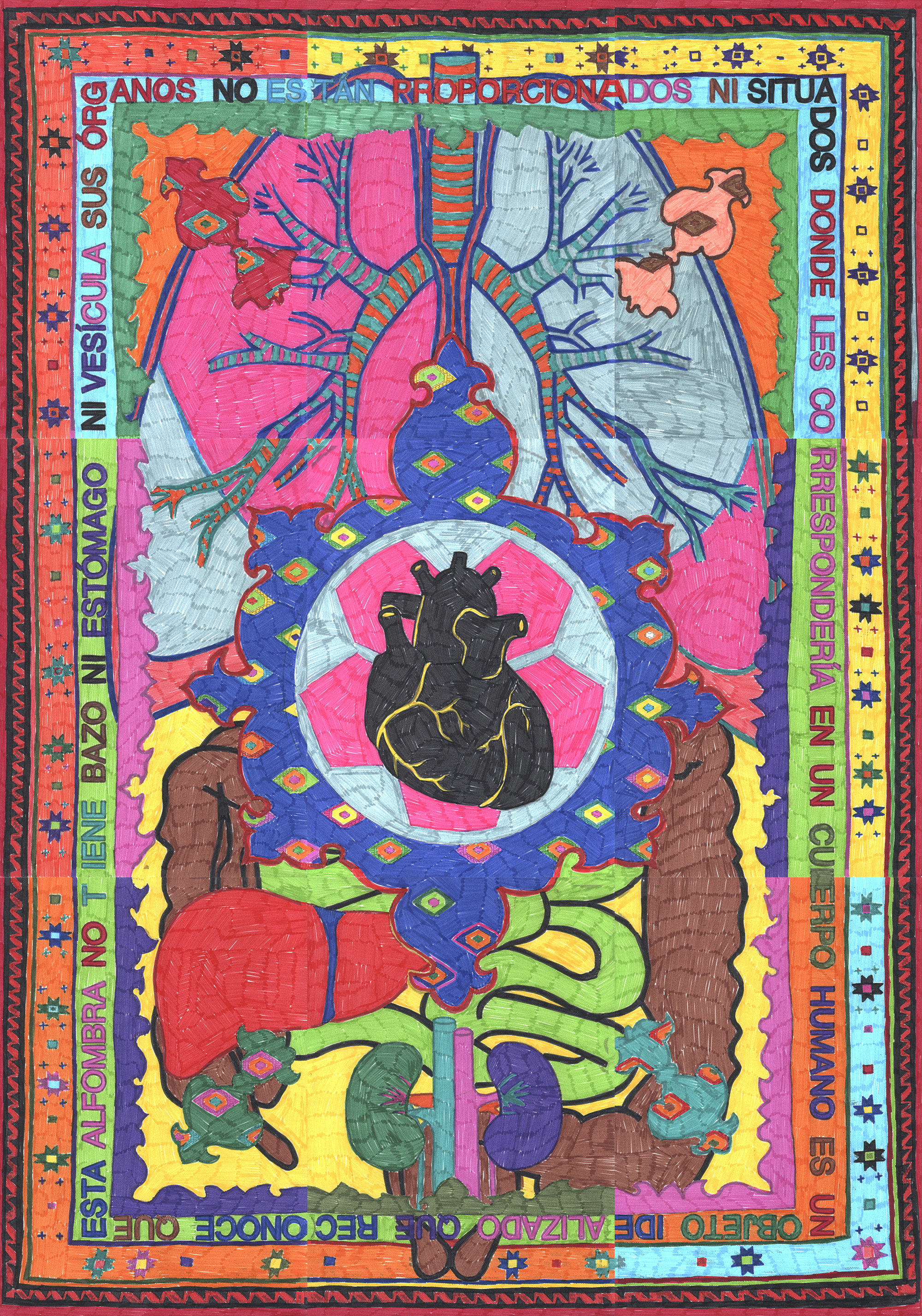

What did you want to express with the project “Paper Carpets”?

Araks: Paper Carpets is a project I’ve been working on in series for the first time. It has always been one work, one technique, one idea. Unlike the exigent project of videos made before, where spectators were expected to watch it slowly because of its density, the Paper Carpets project feels really light but deep at the same time. It’s close to my personality.

What are the two comments (positive and negative) about your art that you will never forget? And in general, does it matter to you what others think about your work?

Araks: Let’s start with a positive one. I don’t always know if I’m doing the right thing or not, so I’m questioning my work all the time and that’s exhausting. Last year when I was graduating from my art school I’ve been doing the best I could with the support of some people who helped me make the installation for my graduation. And I got the diploma with the highest honors from the jury. In France, the members of the jury don’t know you at all. It was important for me to see I had a unanimous highest honours from the jury, but still, it was just an administrative step to get my graduation, so I’m not obsessed with that. But I was happy about that.

The bad one actually is not a bad one, it’s more a “silence” one. A few years ago I decided to sing to an improvisation on the piano in my art school. I decided to show them what I’m doing at home, although it wasn’t conceptual at all. So I played and sang for 30 minutes for the audience (there were a lot of people) but they were silent and I didn’t know if it’s good or bad. It made me really confused. After my performance they were asking whether I’ve conceptualised contextualised my work and for me, it was like a very important moment. I was really touched by that powerful moment and their reaction disturbed me a little bit and that was the worst moment.

What colors would you choose to describe you and your life at the moment?

Araks: Now my life is probably black black black with some very thin lines of pink, red and turquoise. Black is the most elegant colour, the deepest one, probably sad too. Even though sadness about black is just a cultural thing.

Take me home 30 sheets. Dimension of paper carpet: 100x145 cm

Organ carpet 9 sheets. Dimension of paper carpet: 63x89.1 cm

As a female artist: do you think that moving abroad was a breakthrough moment for you as an artist?

Araks: I didn’t choose to move to Spain when I was 13, also I didn’t choose to be born in Armenia. Actually, I was an illegal immigrant in Spain, that wasn’t my choice too. Of course, all this transition from Armenia to Spain is very important for my art. I remember all the seconds, all the parts which seem like a film to me. First I arrived at Ibiza because there was less control and then we took a boat to Alicante which took 6 hours. And I can still remember when we were walking to the boat I saw a big poster of a naked man and a woman. That was my first impression of Spain. I am from Hrazdan, where a lot of people don’t speak about their sexuality. So when I saw the poster I was like “OMG where am I going?”

Then shifting languages. That wasn’t normal for me. I loved mathematics in Armenia but when we arrived in Spain, naturally I didn’t know what to study so I chose translation. Now it all makes sense to me why I did that: it’s all about translation, transition, recreation, retranslation. Spanish culture left its mark on me. The way they’re dressing or communicating with each other. In Spain, people spend a lot of time outside and they speak really loud, as if they want others to look and listen to them. There is some performance in their behavior. They remind me of the characters from Almodóvar’s films. People from different places experience the same things differently. Everything has its part in all of my work.

Education

2017-2018; 2015-2016. Fine Arts MA - ENSAPC National School of the Arts Paris-Cergy, France. Graduated with unanimous highest honors from the jury.

2016. Fine Arts - Central Saint Martins UAL London (Erasmus).

2016-2017. 2018-2019. Armenian studies, Arts and Literature MA - INALCO National Institute for Oriental Languages and Civilizations, Paris.

2014-2015. Visual Arts - University Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne.

2008-2013. Translation and Interpreting (French, Russian <> Spanish) - University of Alicante.

Follow Araks on Instagram to learn more about her work for WOLKAIK In Flight Magazine. And check her website.

By Mary Melkonyan